Author Archives: cielodrive.com

William “Billy” Doyle interviewed by LAPD Lt. Earl Deemer 8/30/69 – Part One

Monday, July 1st, 2013

From the First Tate Homicide Progress Report*

William J. Doyle, Toronto, Canada, No. FPS 230 203-A, male Caucasian, 27, 5-8, 180, brown hair and brown eyes. This suspect has one arrest for Uttering Prescription for Narcotic Drug, two charges. Disposition indicates that he was sentenced to 12 months, case suspended, case appealed. The appeal was allowed, the conviction was squashed and the verdict of acquittal entered. Doyle is a native of Toronto, Canada and a user and smuggler of drugs to the United States.

William Doyle and Tom Harrigan came to Los Angeles in January of 1969, from Toronto, Canada. Doyle arrived first via commercial airline, arriving with an estimated two pounds of cocaine. After his arrival, he took up residence at Cass Elliot’s, 7708 Woodrow Wilson Drive, Los Angeles. Doyle and Elliot, had met while Elliot was making a film in Toronto, Canada, Doyle’s and Harrigan’s hometown. When Doyle arrived, it was obvious to Elliot that he was high on drugs and when he produced the two pounds of cocaine, Elliot told him he would have to leave. It was at this time that Harrigan arrived and the two of them took up residence at 1459 North Rings Road, Los Angeles. From this location, Doyle and Harrigan began to solicit and make friends among various persons in the movie industry. They did this in order to make contacts for the sale of the smuggled cocaine.

Harrigan and Doyle, after moving to Kings Road, sold at least $6,000 worth of cocaine during their first month.

Terrance Cooksley, an 18-year-old houseboy at the Kings Road address remained high for at least the month of February on cocaine supplied by Harrigan and Doyle. Sometime in March, he stole the $6,000 that Doyle and Harrigan had made. He frequented miscellaneous discotheques in the Los Angeles area and spent the money freely or gave it away in the form of large tips to various waiters. Doyle and Harrigan followed him to Stockton, California where they knocked him around and threatened him. They told him to keep his mouth shut and left Cooksley returned to Los Angeles, and in mid March, Doyle and Harrigan took Cooksley, bodily, from the Whiskey-A-Go Go. They rode around in the Hollywood hills, with Harrigan driving. Doyle was in the back seat beating Cooksley with a hammer handle. Harrigan stated it appeared that Cooksley liked the beating and, therefore, they stopped. A crime report was taken; however, Cooksley gave misleading statements and information and there was no prosecution. He did describe Harrigan and Doyle to his father as vicious persons and probably hired killers.

****

In mid March of this year, the Polanskis had a large catered party which included over 100 invited guests. The persons invited included actors, actresses, film directors and producers, business agents for the above-described people, and the Polanskis’ attorneys. Most of the people invited came to the party along with several people who were uninvited. The list of uninvited guests included William Doyle, Thomas Harrigan and Harrison Pickens Dawson. They came to the party accompanied by an invited guest, Ben Carruthers and an unidentified male.

During the party, a verbal altercation ensued involving William Tennant, Roman Polanski’s business agent, and William Doyle. Doyle apparently stepped on Tennant’s foot during this altercation. Dawson and Harrigan joined in the verbal altercation, siding with Doyle. Roman Polanski became very irritated and ordered Doyle, Harrigan and Dawson ejected from the party. Ben Carruthers and the unidentified male that had accompanied him to the party escorted the three men from the property.

****

Doyle and Harrigan became quite friendly with [Wojciech] Frykowski and [Abigail] Folger. This was mainly due to the fact that Frykowski was interested in the known drugs on the market, in addition to future synthetic drugs that were being made in eastern Canada. Doyle and Harrigan told Frykowski that they would obtain the new synthetic drug, MDA, from Canada and allow him to be one of the first to try it. This conversation or agreement apparently took place sometime in the early part of July, 1969, at the Polanski home.

[Witold] Kaczanowski was present at the Polanski home in the early part of July and overheard Doyle and Harrigan tell Frykowski they were going to get him the drug known as MDA. Kaczanowski did not see Doyle and Harrigan after this meeting.

In mid July, Doyle left for Jamaica with Charles Tacot to make an underground film about the effects of marijuana. Harrigan made a trip to Toronto, Canada and brought back a supply of MDA and possibly other drugs via commercial airlines. It is known that he supplied at least a portion of this MDA to Frykowski. It is possible that Frykowski was given this drug by some other emissary two or three days prior to the murder.

* Portions of this police report have been rearranged for chronological purposes.

SATURDAY, AUGUST 30, 1969, TORONTO, CANADA

LT. EARL DEEMER: It’s 11:50 and this is William – what’s your middle, uh —

WILLIAM DOYLE: Joseph George.

LT. EARL DEEMER: William Joseph George

Well, suppose you can give me a little run down just how you became uh – so when you came – first came to Los Angeles.

WILLIAM DOYLE: I believe I first – to the best of my recollection, I first uh. I first came to Los Angeles two years ago.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Two years ago.

And, uh, you stayed up until – did you stay or were you back and forth?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I was back and forth between, Los Angeles and Canada and other places.

LT. EARL DEEMER: And uh, prior to this occurrence, when was the last time you were in Los Angeles? When did you leave Los Angeles?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I believe – I’m trying to recall the exact day – I believe I arrived in Jamaica on the uh, 15th of July.

LT. EARL DEEMER: 15th, so you left with Charles?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I don’t know the dates. And of course, I wasn’t expecting him, but I can find out the dates; ’cause I kept the airline tickets.

LT. EARL DEEMER: And, when did you leave Jamaica?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I left Jamaica.

Excuse me Mr. Deemer, do you remember the day that I came in?

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well you told me uh —

WILLIAM DOYLE: You met me at the airport

LT. EARL DEEMER: — (unintelligible) the day coming back. Uh

I have to look at something.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Ok, I guess you caught my name. It’s Lieutenant Deemer from Los Angeles Police Department.

When you leave – I talked to Charles about this – when you leave Jamaica, what is required, that you uh, pay two dollars or something like that?

WILLIAM DOYLE: When you go to Jamaica they give you – Canadians, Neither Canadians or Americans need a passport to enter Jamaica. When you enter Jamaica they give you a slip. Akin to a visa slip. They take a two dollar – a two dollar and fifty cents head tax, tourist tax. (unintelligible) and keep this with you at all times and turn it in when you leave the island, you get. And you pay two dollars and fifty cents and they stamp it, and turn it into the customs agent as your leaving the island.

LT. EARL DEEMER: And you, uh, originally went down there with Charles to uh, do some work on this?

WILLIAM DOYLE: To collaborate on a film.

LT. EARL DEEMER: ah uh.

Were you in the acting aspect or the, producing, writing or?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I was giving Charles my – he was making a film on the socialogical impact of drugs and culture today, particularly how it deals with the young people. I was with him. He was asking me my opinion of what I’ve saw, what I’ve seen in Hollywood; or wherever I have been. And what my uh – getting some impressions from me, as to, pertinent to the nature of the film.

LT. EARL DEEMER: That was the 18th of the – that you returned from uh, Jamaica. (unintelligible)

WILLIAM DOYLE: That was the day I left then.

LT. EARL DEEMER: And you came directly to, uh?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Non-stop.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Where did you first hear about this, uh?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Learned about it on Saturday at noon from a news broadcast. And the records will show that the telephone lines in the north shore of Jamaica were out that day. And uh, that evening I got through to California and I instructed Cass – told me what happened and I instructed her to call the officers that had been to see her. I believe she did that immediately. And uh, from that time on the Los Angeles Police Department was appraised of my whereabouts, my address and my phone number. Three days after that I read in the paper I was wanted for murder; or in connection with the murder.

I was very nervous. I couldn’t understand it.

LT. EARL DEEMER: And uh, was there anyone else in the party when you left to Jamaica, besides you and Charles.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Charles and I were together

LT. EARL DEEMER: Were there a couple of girls in the uh, group?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yes there were.

They weren’t – they, they didn’t come when Charles and I flew in from – Los Ang- the United States. Both girls were Jamaica nationalists who are, residents of Canada, under working permits who came down to stay with us down there; we had a lovely home; and there were servants there, and a housekeeper, and a maid, and a gardener who were all living in the house.

LT. EARL DEEMER: They’re still there?

WILLIAM DOYLE: They’re there all year round.

LT. EARL DEEMER: They live there?

WILLIAM DOYLE: They live there full time.

LT. EARL DEEMER: You remember – you remember their names?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I do. The housekeeper’s name is Ruth. The maid’s name, is Lesrine. And the gardener is Lesrine’s brother. And his name is Guy.

They perform such functions as, serving meals; making – keeping the house tidy. In other words they were in the house actually living with us. They weren’t out tucked away somewhere. They were, waiting for me.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Now, how long has it been since you uh, met Tom Harrigan?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I do not know when I didn’t know Tom Harrigan.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well, How long has it been since you’ve seen him? Or talked to him?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I haven’t talked to Tom Harrigan since uh, at least a month before I went to Jamaica.

He dropped up to the house – to Cass’ – I was with him.

About a month before I went to Jamaica, I saw him briefly.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Was uh, he in business with you down in Jamaica at one time? Or are you —

WILLIAM DOYLE: Never in Jamaica in business with me. That was here. Tom worked for my father. Tom has never been in business.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Sort of a salesman?

WILLIAM DOYLE: He was a salesman. And he worked for a subsidiary of the (unintelligible) Company.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Was it a telephonic type thing.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yes.

LT. EARL DEEMER: There’s a few names I want to ask you about, uh —

WILLIAM DOYLE: Alright.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Did they, uh – of course you know Tacot, uh. How do you pronounce this last name?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Tac-oh.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Tac-oh.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yeah.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Uh, you’ve know Harrigan all your life.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yes.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Pretty much raised together. How about uh, Deturo?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I met John with Tom. I met him here in Toronto, once. Next time when I met John – I did not know John. I met John – I shouldn’t, I shouldn’t make definite statements like that, excuse me.

LT. EARL DEEMER: To the best of your recollection, is all we ask.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Uh, I met him up in (unintelligible). Uh, I met John more than once up in Toronto. I never knew him. I knew him by sight. Uh, he came to – he showed up in Los Angeles. He seemed to know where to find Tommy. That’s how I met him.

LT. EARL DEEMER: What was your impression of Deturo?

Was he uh – personality wise? How would you feel about John?

Strike you as uh —

WILLIAM DOYLE: He strikes me as uh, what I would uh, call a stand up fellow.

I got John as uh – much more together than a lot of young people I see today. His hair has never been long or over his shoulders; as mine, extends over my ears a bit. He’s not a hippy. He uh, I understand he has a girlfriend, that he’s had for sometime. I, believe uh, he loves kids.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Do you know what he does for a living?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Don’t have the faintest idea.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Ever seen him work?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Never. I don’t – I never, I – as I’ve said I’ve met the man two or three times, and socially. And when I say socially, I mean I don’t know any other way to describe it. I ran into him with people I know. He’s never been in any place that I’ve ever lived, or frequented. And I don’t believe he drinks. If he does, he drinks moderately, because I’ve never seen him in a bar.

LT. EARL DEEMER: How about a man by the name of Hatami?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I’ve heard the name. I believe I’ve met him while at Jay Sebring’s. I believe uh, we’ve shaken hands and said hello. To my knowledge, I’ve never had a conversation with that man.

LT. EARL DEEMER: You uh, ever met Polanski?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I met Roman, on two occasions.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Where was that?

WILLIAM DOYLE: One night at a housewarming party he had.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Up at the Woodstock address – or the uh —

WILLIAM DOYLE: Cielo Drive —

LT. EARL DEEMER: — Cielo Drive?

WILLIAM DOYLE: — Yes. And uh, somewhere else, I can’t recall but it was social – in Hollywood.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Were you uh, familiar with, Sharon – Tate?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yes, I met Sharon.

LT. EARL DEEMER: This was during, uh?

WILLIAM DOYLE: This was early.

Sharon’s a lovely girl. Sharon did not take drugs. Sharon never took drugs, to my knowledge. I never saw Sharon high, ever. And I’m the kind of fellow that notices.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Did she drink, that you’d see?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I never saw her drink.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Uh, how about Debra, Tate?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I can’t recall Debra…yes, I saw Debra Tate once. I went to the Cielo Drive residence again. Wojciech was taking pictures of Pic, for Pic’s composite. Pic at that time, was thinking that he had a chance, to audition (unintelligible) – to read for a part in a film. I’d tell you the name of the producer but I don’t know. I believe Cass may be able to help you there. And uh, and uh Sharon’s sister was there.

LT. EARL DEEMER: When was the last time you talked to Cass?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Four or five days ago.

LT. EARL DEEMER: She still worked up about this?

WILLIAM DOYLE: She’s hysterical.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Mm Hmm. I understand she has uh, I little bit of an emotional problem. Have you ever noticed it?

WILLIAM DOYLE: No.

I mean uh, once again I’ve become short with myself and you, and I apologize for being short with you. I can’t say no so quickly. Everyone I know has emotional problems. I particularly have ones I’m very familiar with. I think Cass is a lovely girl.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Have you ever seen Cass use narcotics?

I already know the answer to it, just uh —

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yes I have.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Ok.

WILLIAM DOYLE: May I ask you something?

LT. EARL DEEMER: Yes.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Is any of my testimony, uh – will my testimony concern whether I was into that.

LT. EARL DEEMER: No. (unintelligible) —

WILLIAM DOYLE: I have nothing – nothing to hide protect or hide, but I don’t want to cause anybody any more undo pain. This secondary investigation has caused a lot of people, a lot of pain, because a lot of people feel that they’re guilty or they have something to hide about something, and go through enormous emotional wringers. This is what Cass is hysterical about.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well, of course —

WILLIAM DOYLE: I don’t want to hurt her but I want to help you with everything I can.

LT. EARL DEEMER: — in this background, we are running into all this drug business. Now, whether if drugs actually had anything to do with the killing, we’ll see. And uh —

WILLIAM DOYLE: I tell you everything I know and you put the picture together because I can’t, I don’t have any of the, any of the – you people obviously have a big puzzle you’re trying to fit together and I’ll just tell you want I can.

LT. EARL DEEMER: We don’t have any interest in drugs per se. That’s been entirely separate from it – for instance, Harrigan told us a great deal about drugs and we gave him a free ride. We’re not really investigating anything that has to do with drugs; only has it has interest in this case.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Can you give me an idea of what Harrigans told you?

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well, hes indicated your uh, part in this to some extent. But again, we told Harrigan that we weren’t interested in —

WILLIAM DOYLE: My part in this?

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well, as far as your part in the drugs. Your use of drugs and you being at these parties, and taking part in it. And of course I know (unintelligible)

WILLIAM DOYLE: I’m not denying, I’m just asking.

LT. EARL DEEMER: All these names dropped out, and so one thing leads to another, to the extent that we are talking to all kinds of people.

WILLIAM DOYLE: I only asked you because Cass has a career and uh, I wouldn’t want to hurt anybody, or cause any more grief to anyone then that’s already been caused by this whole thing.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well uh, if we tried to uh, publish the names of everybody that used drugs in Hollywood uh, you know it would take up a telephone book. We’re not interested in that, frankly.

Uh, a couple more names here – how about a Rinehart, Billy Rinehart?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yes, I know Billy Rinehart.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Ok, do you happen to know where he is now?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I do not.

LT. EARL DEEMER: When was the last time you saw him?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Last time I saw Bill Rinehart he was uh, at Cass’ house. They were talking about doing uh, uh, recording a song; he had written a couple of songs and he was playing them for Cass. But I saw William often, because he came over to the house. A lot of younger musicians, always – Cass’, a lot of people always came to visit Cass.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Is that Billy Rinehart?

WILLIAM DOYLE: That is not.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Is that someone you recognize?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Real light, I can’t tell you. It looks familiar but I don’t know. No, I’d have to say I’ve never seen this person before. But I can’t tell you for sure, it looks very familiar and it’s a very odd angle.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Yeah, it’s taken from down the steps there.

WILLIAM DOYLE: It is a very close likeness to me.

LT. EARL DEEMER: (unintelligible).

WILLIAM DOYLE: Neither of them are me.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Ok, you don’t know this person?

WILLIAM DOYLE: Interesting. Very interesting. Almost reminds me of the company store. Are these two people the same people?

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well, that’s, I think so, yes. But I couldn’t say that definitely.

WILLIAM DOYLE: Well, I can tell you how I know they’re not me. If you blow both of these pictures up and look at the bottom earlobe you’ll notice mine is not attached. His ear – there are two kinds of ears.

LT. EARL DEEMER: He’s got his hair styled in a that fashion.

WILLIAM DOYLE: I’ve had my hair over my ears, but it never looked like that. My hair is naturally like it is here. His ear is going directly to his cheek like this, you’ll notice. Mine don’t.

This one, I’ve seen.

LT. EARL DEEMER: But you don’t know —

WILLIAM DOYLE: No.

LT. EARL DEEMER: — a name? Ok, that’s uh, Parker – Parker, the uh, karate —

WILLIAM DOYLE: I know him.

LT. EARL DEEMER: — uh, Sebring.

Did you know Pic —

WILLIAM DOYLE: Yup.

LT. EARL DEEMER: — when he was uh, dressed like that?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I did.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Were you um, fixing yourself like this when uh, when you knew him?

WILLIAM DOYLE: All the time.

LT. EARL DEEMER: Well uh, You don’t know where Rinehart lives in L.A.?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I do not. I believe he lives with his family.

As far as (unintelligible) he’s in the beverage business. He also is often found with the Gemini Twins; two girls who do recording, like the Blossoms.

LT. EARL DEEMER: How about a Randy Greenwell?

WILLIAM DOYLE: I know a Randy, but I don’t know a last name. He has a wife that bought him a bentley. Same man? Red hair? Works in a beauty salon? I know him.

Linda and Abilene: Lost Films Of Herschell Gordon Lewis

Friday, June 21st, 2013

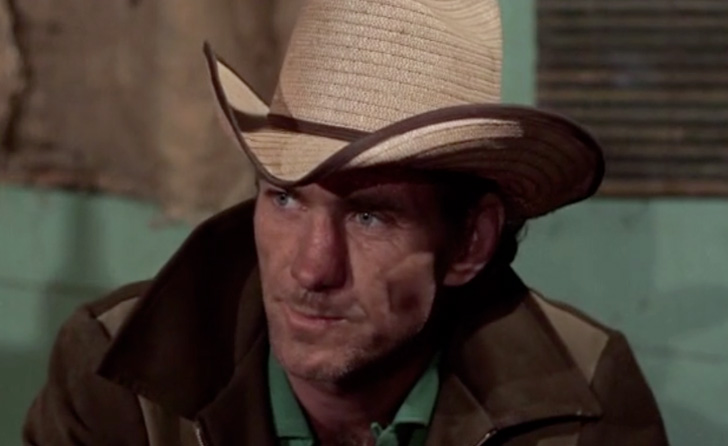

Bill Vance drinking in the Longhorn Saloon in the film Linda and Abilene

Jun. 21 – The Lost Films of Herschell Gorden Lewis, a 2-disc BluRay/DVD combo pack released in January, features three recently restored sexploitation films including the erotic western Linda and Abilene. Filmed at the Spahn Movie Ranch in 1969, Linda and Abilene tells the story two siblings, Abilene and Tod, who after being orphaned on their western farm, become attracted to each other. The confused Tod fleas to a nearby town where he meets Linda, a local bar girl, and begins a sexual relationship with her, while a rough cowboy, named Rawhide, sexually assaults Abilene leading Tod wanting revenge despite Linda’s wariness and growing compassion for Abilene.

The movie, which features fantastic color footage of Spahn’s Ranch, was filmed while the Manson Family was living there. According to liner notes, “Lewis claims that he and the crew ‘thought little or nothing of’ the unusual people hanging around the location, even when seemingly the entire Family showed up on set to peep on the lesbian sex scene as it was being filmed. They were just a bunch of ‘goofy kids…stoned out of their heads,’ according to Lewis.”

But perhaps the most interesting thing about the film is that it stars the Manson family associate, Bill Vance. Although he has no lines, Vance is a prominent extra within the film and there are several close ups of him.

The film also provides possible answers as to why some at Spahn would later say that Sharon Tate had visited the ranch. Shortly after the Tate-LaBianca murders were tied to the Manson family in December of 1969, there were reports that an actress named Sharon had visited the ranch earlier that year. This led to the speculation that the actress was Sharon Tate. Perhaps Linda and Abilene was the cause of the confusion, because the part of Abilene is played by the actress Sharon Matt. Could she have been the actress that some at Spahn would later confuse to be Sharon Tate?

Special thanks to BlueJay for finding this.

Leslie Van Houten Denied Parole For The 19th Time

Wednesday, June 5th, 2013

Jun 5 – Leslie Van Houten was denied parole for the 19th time today in a hearing at the California Institute for Women in Corona, California. She will not be allowed another hearing for five years.

Van Houten, the youngest of those responsible for the Tate-LaBianca murders, was sentenced to death in 1971 for her part in the August 10, 1969 murder of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. The following year, Van Houten saw her sentence commuted to life after the California supreme court outlawed the death penalty.

On Friday, August 13, 1976, a California court of appeals ruled that Van Houten was denied a fair trial because her attorney Ronald Hughes had disappeared while the trial was in progress. The appeals court reversed Van Houten’s conviction and ordered her to be retried.

“She’s older — a mature woman now. People change their minds even when not in prison, and she’s changed hers,” said her attorney Maxwell Keith in January of 1977. “She’s forsaken the Manson Family. She’s back with her own now.”

That same month, Keith attempted to get a temporary restraining order issued against the CBS Television Network that would’ve prevented the network from airing the movie Helter Skelter.

“It depicts her as a very depraved, malevolent young lady, an unrepentant murderer,” said Keith. “That’s not fair. She is back here for retrial and she is presumed innocent.”

In February of that year, Leslie told journalist William Farr that the Manson family was never as big as the media made it to be.

“There really were only about 10 girls and three guys although people came and went,” said Van Houten.

“He used to be good with cards, you know, play tricks with cards. Charlie would put something in our mind and because he was quick with his hands and wit, we would sort of think we had seen a miracle.”

Van Houten told Farr she was embarrassed to admit she actually believed in Charlie’s Helter Skelter and that she continued to have nightmares about the murders.

“I know that I did something horrible…I don’t expect people to forgive me but I hope eventually they will give me a chance.”

The retrial began on Monday, April 18, 1977 at the new courthouse across the street from the Hall of Justice. The mood was completely different than it had been seven years earlier. Van Houten did not arrive to court smiling or singing as she had in 1970. There were no vigils on the street corners below.

Testimony began the following day, with Deputy District Attorney Stephen Kay first calling Susan Wolk to the stand. Wolk, the 28 year-old daughter of Rosemary LaBianca testified that upon arriving home from a water skiing trip, her brother Frank phoned her, concerned about something at their parents house.

Along with her then-boyfriend Joe Dorgan, Wolk met with Frank and went to the house.

“Joe and Frank went in first,” continued Wolk. “I walked into the kitchen and dining area.” Her brother and Dorgan stopped suddenly and wouldn’t let her continue into the living room. The two turned Wolk around towards the kitchen and out the back door.

Leslie Van Houten sat motionless behind a counsel table, trying her best not to make eye contact with the physical evidence or Wolk. Dorgan took the stand next and told the jury what he had seen in the living room at 3301 Waverly Drive.

“Newspapers were strewn around,” said Dorgan, “Leno was lying between the coffee table and the couch with something protruding from his chest.”

By days end, the jury had also heard testimony from the first officer to arrive at the residence, William Rodriguez, as well as the last person to see the LaBiancas alive, newspaper vendor John Fokianos.

The following week, Linda Kasabian returned and gave an unemotional account of the Tate murders “as if she were describing a traffic accident for which she had no responsibility,” wrote one journalist.

“[Leslie] is being tried for the Sharon Tate murders and she wasn’t even there,” an angry Maxwell Keith told reporters outside of court.

Leslie, dressed in a pink blouse and plaid pant suit, took the stand on Thursday, May 5. She testified that LSD had been smuggled into jail and she took acid throughout her original trial. According to Van Houten, Manson had thrown a razor blade across the table and instructed the girls to carve Xs into their foreheads.

She continued, saying that Manson had told her she would need to testify. Van Houten said that she was visited in jail with instructions for her to say that Manson hadn’t been around at the time of the murders and didn’t have any knowledge of them.

On Thursday, June 9, Leslie Van Houten was back on the stand, talking about life with the Manson family.

“It was a mellow situation,” said Van Houten. “It was an easy, slow life. No one had any goals they were trying to accomplish other than to tune in…to try to get rid of old thoughts, to live only for the moment.”

Leslie’s testimony continued the following week when she told the jury she that at the LaBianca residence, Charles “Tex” Watson had handed her a knife and told her to do something, and that she stabbed Rosemary LaBianca about 14 times in the lower back.

“I know I just kept doing it over and over again,” said Van Houten.

Asked by her attorney how she felt. Van Houten said, “I felt like the shark, like a primitive animal some kind of wild cat that had caught a deer.”

When court resumed the following day, Leslie testify she had been offered and turned down immunity while in Inyo County in November of 1969. The deal according to Van Houten was offered to her by LAPD Sgt. Michael McGann and included immunity, around the clock security and possibly even the $25,000 of reward money. When asked why she didn’t accept the offer, Van Houten responded, “I felt kind of like I was sitting in the seat of Judas.”

Later in the trial McGann testified that when he discussed immunity with Van Houten, he was talking about arson charges, not murder.

Throughout the trial, Maxwell Keith called five psychiatrists to the stand. All testified that Van Houten was mentally ill at the time of the murders and incapable of premeditation, the requirement for first degree murder.

Their testimony was however contradicted on June 21, when Stephen Kay called Dr. Joel Fort.

“She did harbor malice and did manifest an intent to kill another human being,” said Dr. Fort.

Dr. Fort explained his opinion based on that fact that Van Houten had discussed killing before the murders and then made efforts to hide them after they had be committed.

On June 27, Maxwell Keith played a tape recorded interview Charles Manson did with Dr. Fort. Manson continued to claim he did not direct Van Houten and the others to kill the LaBiancas. However, Manson did admit somewhat that he had influence on her.

“Certainly I had influence over her,” said Manson on the tape. “I have influence over everybody I meet. If I showed her the way to herself, and she decided she wanted to do something, no one’s going to wind her up and make her do it

“Man, I’ve seen the broad only a few times,” he continued “I never paid that much attention to her. I’m telling you the truth. I never had that much effect on Leslie because I never — how can one guy have effect over 30 to 50 broads?”

The recording also somewhat contradicted the defense’s contention that excessive drug use had led to Van Houten’s diminished capacity.

“We were not all that much into drugs,” said Manson. “Everybody said we were but that’s not true. The truth was we took acid whenever it was around. Sometimes it would be maybe once a week, sometimes once a month, sometimes three times a month.

“We weren’t into speed or hard drugs. A little hash and a little grass. Just a blaze kind of get-loaded social thing.”

After 10 weeks and 38 total witnesses, testimony had ended.

“The people of the state of California have not only proved Leslie van Houten participated in two of the most brutal murders in American crime,” Stephen Kay said in his final argument, “but we have proved those are murders of the first degree.”

The following day Maxwell Keith told the jury that members of the Manson family were sick and argued that Leslie was guilty of manslaughter not first degree murder.

The jury began their deliberations on Friday, July 10.

After a week of deliberations the jury asked to listen to the 4 hour recording of Leslie and Sgt. McGann, as well as Dr. Fort’s May 1976 interview with Charles Manson. A week later the jury appeared in court to ask legal questions about diminished mental capacity.

On Monday, July 25, after two weeks of deliberations, a male juror had to be replaced because of illness. Judge Edward Hinz instructed the jury that they would need to disregard their previous 13 days of deliberations and start over.

A mistrial was declared on Saturday, August 6, when after 25 days of deliberations the jury was still deadlocked. The split, according to foreman Bill Albee, was seven for first degree murder and five for manslaughter.

Leslie Van Houten was freed on a $200,000 bond on Tuesday, December 27, 1977. Her freedom was spent with friends and family who helped her get reacquainted with the world outside prison walls. Leslie lived a low-key life and got a job working as a legal secretary.

Her third trial began in the spring of 1978. This time Deputy District Attorney Stephen Kay changed his strategy, attempting to get Van Houten convicted on murder committed in the act of robbery because she had taken coins and clothes from the LaBianca residence.

On Wednesday, July 5, 1978 a jury found Leslie Van Houten guilty on two counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder and she was sentenced to three concurrent life terms a month later.

Van Houten was returned back to prison on August 17, 1978 and with a credit of eight years and 20 days time served, she was immediately eligible for parole. Her first hearing was in January of 1979 and although she was denied, she received favorable reviews from prison psychologists and prison staff.

Leslie’s third parole hearing was held on Wednesday, April 22, 1981. The three member board commended Van Houten on her positive adjustment, but felt she needed to serve more time due to the nature of the crime. Leslie’s attorney, Paul Fitzgerald, told the panel that they ought to be ashamed of themselves.

“I find your decision intellectually dishonest and the worst kind of pandering to public sentiment,” said Fitzgerald.

“I feel in a lot of ways I’m being undermined by popular anger. I feel like I’ve become a political commodity,” said the 31 year-old Van Houten. “The name Leslie Van Houten next to Charles Manson’s name can get people elected or not elected. I know that.”

In Fullerton, California, Rosemary LaBianca’s brother, H. Russell Harmon, was happy to hear the news.

“It makes me feel that our justice system is turning around,” said Harmon. “I think criminals are going to have to serve some time and are not going to get off so easy.”

Hearing after hearing, years became decades and nothing seemed to change. Panel after panel praised Van Houten’s progress behind bars but ultimately denied her release because of the nature of the crime and Van Houten’s unstable social history. For decades it seemed as though her release was just one or two years away. But that day never came.

Van Houten’s release had been opposed by the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office since she became eligible for parole in 1978. Deputy District Attorney Stephen Kay – who assisted in her original prosecution, and was the lead in her two retrials – attended her parole hearings until he left the D.A.’s office in 2004.

When friends of Leslie began collecting signatures petitioning for her release, Kay enlisted the help of Sharon Tate’s mother Doris Tate. Kay and Tate together worked on their own campaign collecting several hundred thousand signatures from people opposing Van Houten’s release. Doris Tate went on to become a powerful victim’s rights advocate and campaigned the cause up until her death.

The LaBianca family has opposed Van Houten’s release as well. Leno LaBianca’s nieces and nephews have regularly attended Van Houten’s hearings making victims impact speeches.

In 2006, Leno LaBianca’s nephew John DeSantis read a letter from Leno’s eldest daughter Cory. In the letter, Cory LaBianca related to the board fond recollections she had from time spent with her family at 3301 Waverly Drive and how those memories were fractured by the murders.

“Can you imagine how we must feel having that nightmare interwoven with our most cheeriest childhood memories? We can do nothing to change the events of 37 years ago or to erase those horrible memories from our hearts and minds,” wrote LaBianca. “I ask you, please, do not make a mockery of what we love with your decision here today.”

Van Houten, now 63, has been a model prisoner excelling in countless prison programs during her lengthy incarceration. Her one and only rules infraction occurred in 1976 and is no longer even in her file. Her many supporters both in and outside of prison have argued that Leslie should’ve been released decades ago. Leslie lost her closest supporter in 2012 when her father, Paul Van Houten, passed away at the age of 93.

While Van Houten has an exemplary post-conviction record, she like many others associated with the Manson murders remain unsuccessful in separating themselves from the everlasting impression left by the murders and unforgettable trial that followed.

Leslie Van Houten will not be allowed another hearing until 2018.

Three Murders Listed In Warrant For Watson Tapes

Friday, May 31st, 2013

May 31 – Three murders were listed in the search warrant issued last year for the Tex Watson/Bill Boyd recordings. The sealed warrant, exclusively revealed to Cielodrive.com earlier this week, gave insight into the behind-the-scenes actions taken by the LAPD to acquire the 43 year-old tapes.

The Los Angeles Police Department last October, disclosed their investigators believed that the decades-old taped conversations between Charles “Tex” Watson and his attorney, could possibly link a dozen unsolved homicides to the Manson family. However, the search warrant issued for the tapes that same month only mentioned three murders, none of which occurred within the LAPD’s jurisdiction.

Of the three murders mentioned in the warrant, only two were specifically named – Karl Stubbs and Fillipo Tennerelli.

In November of 1968, friends of 80 year-old Karl Stubbs found him severely beaten in front of his home in Olancha, California. Stubbs was described by friends as a religious man who befriended anyone he came upon. Shortly before his beating, Stubbs was seen with a group of hippie types and was acting out of character. Stubbs was still alive when he was found, but died later in the hospital. Before his passing, Stubbs told investigators that he was beaten by 2 young men and 2 young women, who giggled the entire time they beat him.

The body of 23 year-old Fillipo Tennerelli was discovered in a Bishop, California hotel room on Wednesday, October 1, 1969. Tennerelli died from a shotgun wound to the head and his death was, and always has been, ruled a suicide. Weeks after Tennerelli’s death, the California Highway Patrol reported finding his abandoned Volkswagen in the Panamint Valley, north of the Barker Ranch. According to reports, blood was discovered both in and outside of the vehicle, leading some to suspect that Tennerelli’s death was not a suicide.

According to the warrant, the LAPD became interested in the two cases after reading the Desert News article, More Manson Mysteries in Inyo County. The 2008 article, written by Tom Weeks, covered the still lingering suspicions surrounding both the Stubbs and Tennerelli deaths.

The third murder listed in the warrant is that of an outlaw biker. The warrant doesn’t identify the biker by name, but does identify LAPD’s source for the information – a 2008 taped interview Bill Boyd did with author Tom O’Neill.

The LAPD became aware of the tapes in March of 2012, after the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office was contacted by Department of Justice Trustee Linda Payne. Payne had been assigned with the task of liquidating the assets of the law firm Boyd/Veigel after the firm went bankrupt in December of 2009. Bill Boyd, had died in August of 2009, suffering a heart attack while running on his treadmill. While going through the firms assets Payne found two boxes of legal files and 8 cassette tapes pertaining to the Charles “Tex” Watson case.

Watson was arrested in McKinney, Texas on November 30, 1969 after California issued a warrant in connection to the seven Tate-LaBianca murders. Three days later, Watson retained the law firm of Boyd, Veigel and Gay to represent him in and signed over all of his property to the firm. Bill Boyd fought Watson’s extradition to California for nearly a year before the appeal was denied by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black on Friday, September 11, 1970.

Payne contacted both Watson and the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office about the files and tapes. On March 19, 2012, the LAPD sent Department of Justice Trustee Timothy O’Neal a formal request for the tapes. Payne filed a motion, asking for a court order to turn over the recordings to the LAPD.

A hearing was held in Plano, Texas on May 31, 2012. Watson’s lawyer argued that the tapes were protected by attorney/client privilege. O’Neal, however contested the claim and introduced into evidence a document signed by Charles Watson in September of 1976 that waived his attorney-client privilege. The agreement signed by Watson, allowed for Boyd to sell certain things in order to raise money for his legal defense bill.

Copies of the recordings were sold in 1976 to Chaplin Ray Hoekstra for $49,000. The recordings became the basis for Watson’s book with Chaplin Ray, Will You Die For Me?

Judge Brenda Rhoades ruled against Watson at the conclusion of the hearing, stating that he had failed to prove that the attorney-client privilege still existed. Rhoades ordered the tapes be turned over to the LAPD.

Both Watson’s attorneys and Watson himself appealed Judge Rhoades’ order in June. Watson filed a pro se motion with the court requesting the LAPD only be allowed to listen to the tapes and asked the tapes then be turned over to his attorneys.

According to the search warrant, LAPD homicide detective Dan Jenks met with the author Tom O’Neill in July of 2012. In the meeting, O’Neill let Jenks listen to the 2008 interview the author recorded with Boyd. In it, Boyd discussed having approximately twenty hours of taped recordings of Watson discussing the Tate-LaBianca murders. Boyd also revealed that Watson also discussed other murders committed by Charles Manson, including the murder of a biker.

That same month, Jenks contacted detective J.D. Ross in Fort Worth, Texas, requesting assistance in recovering the tapes. Jenks had learned from Payne that the tapes were locked in a safe at her residence. With information supplied to him from Jenks, Ross put together a warrant.

The warrant, which was signed by Judge Michael Snipes on October 3, 2012, called for the search and seizure of all forms of audio recordings within the residence of Linda Payne.

The warrant was blocked two days later by Judge Richard Schell. According to Schell’s order, the LAPD had not offered any explanation as to why the bankruptcy appeal should be circumvented.

Almost six months later, Judge Schell denied Tex’s appeal, stating that Payne was within her right to turn over the tapes because Watson had signed over all of his possessions to Boyd to pay his legal fees. Watson’s only legal right to the tapes was the attorney/client privilege, which he also signed away in the book deal. Concluding his ruling, Schell wrote, “Watson clearly states that he has no objection to the LAPD listening to the contents of the cassette tapes. Such statement alone constitutes a waiver of the attorney/client privilege.”

The LAPD last week revealed that they had finally flown to Texas to take possession of the tapes. The tapes were turned over to the Scientific Investigation Division who made digital copies and homicide detectives as well as the District Attorney’s Office have begun analyzing their contents. The tapes will not be disclosed to the public at this time.

Audio Archives: Manson & Hypnotism

Saturday, April 6th, 2013

Apr. 8 – For this installment of the Audio Archives series, we will listen in on conversations with a pair of doctors regarding the power of hypnosis. This tape was not marked so I don’t know the names of the doctors, the interviewer or whether he is from LAPD or the District Attorney’s office. The tape was also not dated, but the conversation seems to indicate it took place in December of 1969, shortly after the indictments. At that time, Susan Atkins’ attorney Richard Caballero was telling the press that Susan was among several followers who were under Charles Manson’s “hypnotic spell.”